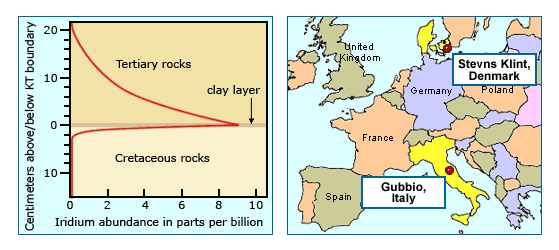

The results of the iridium analysis were quite clear and completely surprising. The team (which also included chemists Helen Michel and Frank Asaro) found three parts iridium per billion — more than 30 times what they had expected based on either of their hypotheses, and much, much more than contained in other stratigraphic layers! Clearly something unusual was going on at the time this clay layer was deposited — but what would have caused such a spike in iridium? The team began calling their finding “the iridium anomaly,” because it was so different from what had been seen anywhere else.

Now Alvarez and his team had even more questions. But first, they needed to know how widespread this iridium anomaly was. Was it a local blip — the signal of a small-scale disaster restricted to a small part of the ancient seafloor — or was the iridium spike found globally, indicating widespread catastrophe?

Alvarez began digging through published geological studies to identify a different site that also exposed the KT boundary. He eventually found one in Denmark and asked a colleague to perform the iridium test. The results confirmed the importance of the iridium anomaly: whatever had happened at the end of the Cretaceous had been broad in scale.

The iridium test revealed that an assumption Alvarez and his team had made about iridium deposition at the KT boundary was incorrect. To learn more, visit Making assumptions.