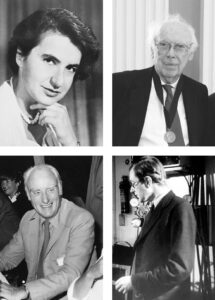

After unraveling the structure of DNA, all four researchers continued to study genetics and molecular biology, although along their separate paths. Wilkins, Watson, and Crick went on to collect additional evidence on DNA’s structure, examine how DNA copies itself, and investigate the genetic code inherent in the DNA molecule. Sadly, Franklin’s research was cut short when she died of cancer — just five years after the landmark Nature publication. This also meant that Franklin missed out on many of the honors awarded for their discovery, including the possibility of a Nobel Prize — which cannot be awarded posthumously.

Despite her early death, Franklin’s work, along with that of the others, has earned a permanent place in our accumulated scientific knowledge. Genetic researchers today still build on the foundation laid by these half-century old ideas and findings. If we trace the roots of today’s cutting-edge technologies like DNA fingerprinting, genetic engineering, and genome sequencing back in time, we will find ourselves once again in the X-ray diffraction lab at the University of London and tinkering with models at Cambridge. And continuing even further back in time, we’ll encounter the community of researchers who set the stage for this discovery by developing X-ray diffraction techniques and by uncovering those first puzzle pieces that inspired Wilkins, Franklin, Watson, and Crick to join the race and chase down the double helix. With many open questions involving DNA, its structure will continue to be a key piece of evidence in many new discoveries yet to come.

Though the discovery of the structure of DNA is frequently attributed to Watson and Crick, the story behind this discovery highlights just how indebted to other researchers they were. Reliance on the clues discovered by others is a key theme, not just of this story, but of the process of science in general. Science is too big a job and involves too many complex ideas for any one person to tackle a problem in complete isolation. Even the few scientists who work alone on a day-to-day basis rely on the cumulative knowledge of the scientific community as a starting point and contribute their findings to this knowledge base so that others can build upon them. Because of science’s collaborative nature, communication — sharing pieces of the puzzle — has played a critical role in many scientific discoveries. As we saw in the race for the structure of DNA, science works not solely through the brilliance and good fortune of a few individuals, but through the work of a diverse community.

Though the discovery of the structure of DNA is frequently attributed to Watson and Crick, the story behind this discovery highlights just how indebted to other researchers they were. Reliance on the clues discovered by others is a key theme, not just of this story, but of the process of science in general. Science is too big a job and involves too many complex ideas for any one person to tackle a problem in complete isolation. Even the few scientists who work alone on a day-to-day basis rely on the cumulative knowledge of the scientific community as a starting point and contribute their findings to this knowledge base so that others can build upon them. Because of science’s collaborative nature, communication — sharing pieces of the puzzle — has played a critical role in many scientific discoveries. As we saw in the race for the structure of DNA, science works not solely through the brilliance and good fortune of a few individuals, but through the work of a diverse community.

- Knowing the structure of DNA laid the groundwork for many modern scientific and medical breakthroughs. To learn more about how science affects our everyday lives, visit What has science done for you lately? To learn more about previous research and technological advances that laid the groundwork for solving the double helix, visit Science and technology on fast forward.

- Unraveling the structure of DNA is a classic example of the process of science in action. To learn more about what features make this investigation scientific, visit The science checklist applied: Solving DNA’s double helix.

Use this story to introduce your students to the Science Flowchart. Check out the middle school or high school version of the activity.

Popular and historical accounts:

- Maddox, B. 2003. The Dark Lady of DNA. London: HarperCollins.

- Watson, J.D. 1969. The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA. New York: Mentar Books.

A few scientific articles:

- Avery, O.T., C.M. MacLeod, and M. McCarty. 1944. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of Pneumococcal types. Journal of Experimental Medicine 79:137-159.

- Franklin, R., and R.G. Gosling. 1953. Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate. Nature 171:740-741.

- Watson, J.D., and F.H.C. Crick. 1953. A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 171:737-738.