These tools can help you reinforce key concepts regarding the nature and process of science with your students:

The Science Checklist examines what makes science science — the key features that set science apart from other human endeavors. Suggested use by students: The checklist was developed to help people distinguish scientific investigations from non-scientific ones. This concept can be introduced to students at this level in a variety of ways:

The Science Checklist examines what makes science science — the key features that set science apart from other human endeavors. Suggested use by students: The checklist was developed to help people distinguish scientific investigations from non-scientific ones. This concept can be introduced to students at this level in a variety of ways:

- Have students read about scientists and their work and apply the science checklist. See Studying variable stars and Solving DNA’s double helix for examples.

- Provide examples of different sorts of investigations (e.g., SETI’s studies of astrobiology vs. those of the National UFO Reporting Center). Have students research the characteristics of those investigations and apply the checklist to them to see how scientific they are.

- Have students read and discuss the following two articles: Astrology: Is it scientific? and Studying variable stars. Ask them to apply the Science Checklist to determine how scientific each is.

- Print out a short article on the discovery of the dense, positively charged, atomic nucleus. After introducing and discussing the Science Checklist, have your students read the story and figure out how it measures up to the checklist. Have a class discussion about this, or have students write up their responses individually.

The Science Flowchart provides a representation of how science really works. You may want to download a copy of the flowchart poster, hang it in your room, and underscore connections to the flowchart components throughout the school year. See Introducing the Science Flowchart for ways to introduce the Science Flowchart to your students. Suggested use by students: The Science Flowchart can provide a good reference for your students (1) to make elements of the process of science explicit, and (2) to help them reflect on their scientific approach to investigations of their own.

The Science Flowchart provides a representation of how science really works. You may want to download a copy of the flowchart poster, hang it in your room, and underscore connections to the flowchart components throughout the school year. See Introducing the Science Flowchart for ways to introduce the Science Flowchart to your students. Suggested use by students: The Science Flowchart can provide a good reference for your students (1) to make elements of the process of science explicit, and (2) to help them reflect on their scientific approach to investigations of their own.

- Have students design the procedures for a short investigation. Students can describe how their procedures illustrate various parts of the process of science and discuss the different pathways followed.

- Have students plan a long-term investigation. Students will address a specific question, test hypotheses, identify and describe variables, make use of a control group. Students can provide a written report that includes methods used, data collected, a summary and interpretation of the data, and a list of resulting questions. Students can reflect on the process of science by charting their pathway on the Science Flowchart. For example, see Design your very own science experiment.

- Have students read a recent news story (e.g., Forever chemicals no more?) and apply the flowchart to track the process of science.

- Have students read about scientists and their investigations (e.g., Asteroids and dinosaurs: Unexpected twists and an unfinished story. Students can chart the pathways of the different investigations and discuss how and why their courses differed.

- Select a series of videos from a source such as Science Friday (e.g., Surveying the Northern Lights or The Lake Sentinel) for your students to watch. Ask them to identify the connections to the Science Flowchart.

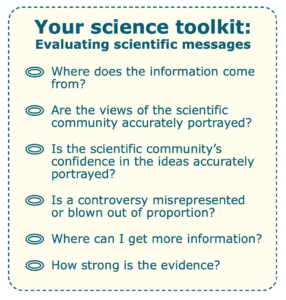

Your Science Toolkit provides a set of questions that can help your students apply critical thinking skills, evaluate media messages about science, and improve their own decision-making. When considering a scientific message or policy, students should be encouraged to ask how we know this and to consider sources of information, quality of evidence, and potential biases and misrepresentation. Suggested activity for students:

Your Science Toolkit provides a set of questions that can help your students apply critical thinking skills, evaluate media messages about science, and improve their own decision-making. When considering a scientific message or policy, students should be encouraged to ask how we know this and to consider sources of information, quality of evidence, and potential biases and misrepresentation. Suggested activity for students:

- Gather examples of reports in the media that make a scientific claim. Ask groups of students to analyze the reports based upon the Toolkit. Begin a bulletin board on Scientific Claims, encouraging students to bring in their own examples of science spin or misrepresentation.

- Have students look at science articles in the popular press to find examples referencing the tentativeness of scientific ideas (e.g., “Numerous uncertainties remain regarding …”) or the views of the scientific community regarding the idea (e.g., “Some scientists believe that …”). Is the tentativeness of the idea exaggerated, underplayed, or justified? Discuss each example.

- Look for “Hype Headlines,” such as Miracle of gene therapy right around the corner, and discuss with students. Start a bulletin board of examples that students find in the print media.

- Find examples of newspaper articles where scientific controversies are mentioned. Discuss the validity of the claim of controversy. Discuss the benefits of true scientific controversy.

- Have students Google a topic such as hamburger nutrition and find examples of both reliable and unreliable resources. Ask them to explain their reasoning.

- Have students offer examples of circumstances in which they or a member of their family has needed to evaluate scientific claims to make a decision (e.g., purchasing a new car). Ask students to explain how they investigated the claims and made their decision.

- The section of Understanding Science 101 that addresses the nonlinear nature of the process of science is available as a pdf, which you can use as a student reader. An effective way to use this tool would be to have students read it and discuss it at the beginning of the semester and then refer back to the document throughout the semester as students encounter examples of these concepts in context.