When Lynn Margulis enrolled at the University of Chicago in 1953, she had planned on becoming a writer. It wasn’t until she took a required science class that she developed a passion for biology. In this course, students read the original works of great scientists instead of a textbook. Gregor Mendel’s classic pea plant experiments captivated Margulis. It was the beginning of a life-long fascination with genetics and heredity.

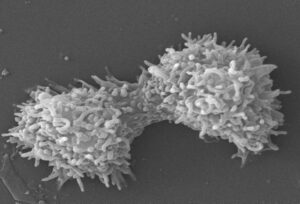

She decided to study these topics for her masters degree at the University of Wisconsin. It was there that she first watched amoebae under the microscope, observing the way they engulfed their food and reproduced by dividing in two. First, the amoeba changes its shape, pulling its blob-like form into an almost perfect sphere. Then the nucleus, the structure that carries the cell’s genetic material, splits in half. After that, the whole cell starts to split, pinching into two separate cells, each with a nucleus and all the other cell structures it needs to live as an adult amoeba.

Around the same time, Margulis began to notice the strangely independent behavior of mitochondria, the structures within cells that provide energy by breaking down food molecules. Even though mitochondria are just parts of the cell, they seemed to reproduce the same way that whole amoebae did — by splitting in two! Because mitochondria were about the same size and shape as some kinds of bacteria, and since bacteria also reproduce by dividing in two, Margulis couldn’t help thinking how much this cell structure, or organelle, behaved like an independent bacterium.

To learn more about the early stages of a scientific investigation, visit our section on Exploration and discovery.