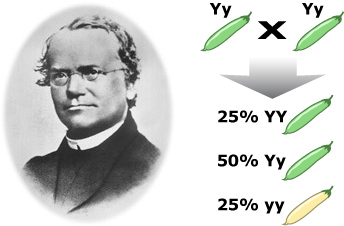

Margulis’ research followed in the footsteps of one of the scientists who had inspired her to become a biologist in the first place. With his peas, Gregor Mendel had shown that genetics was predictable; if you know what genes parents have, you can predict what genes their offspring are likely to have. Later research explained why: genes are located on DNA and DNA follows strict rules when it is copied and passed to offspring. However, at the time, scientists were discovering more and more cases of inheritance that broke Mendel’s laws. How could this be? Margulis decided to try to find out.

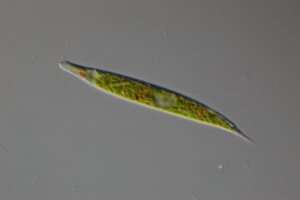

She, along with many other scientists, suspected that cells might have DNA outside of the nucleus and that this DNA might not follow the same rules of inheritance that nuclear DNA does. Margulis’ first research was on Euglena, a single-celled eukaryote. She found that it had DNA inside its chloroplasts, not just in its nucleus. What was the DNA doing there? Was it responsible for any of the traits that seemed to break Mendel’s laws? While considering these questions, Margulis remembered the endosymbiotic hypothesis. She knew that chloroplasts reproduce by splitting in two, as bacteria do — and as the mitochondria that she had observed earlier do. And now she was sure that chloroplasts also had their own DNA. Suddenly, she was captivated by a new question: If chloroplasts contain their own DNA and reproduce by splitting in two, could it be that these organelles really were once free-living bacteria??

Margulis began to explore the idea in earnest. She didn’t do any new research beyond her initial investigations of chloroplasts’ DNA, but she did read about other scientists’ research to find the most up-to-date evidence relevant to her hypothesis. She found that many scientists had made observations that would make perfect sense if eukaryotic cells had evolved via endosymbiosis.

Before we examine the evidence she presented, let’s look at her new, expanded version of the older hypothesis.