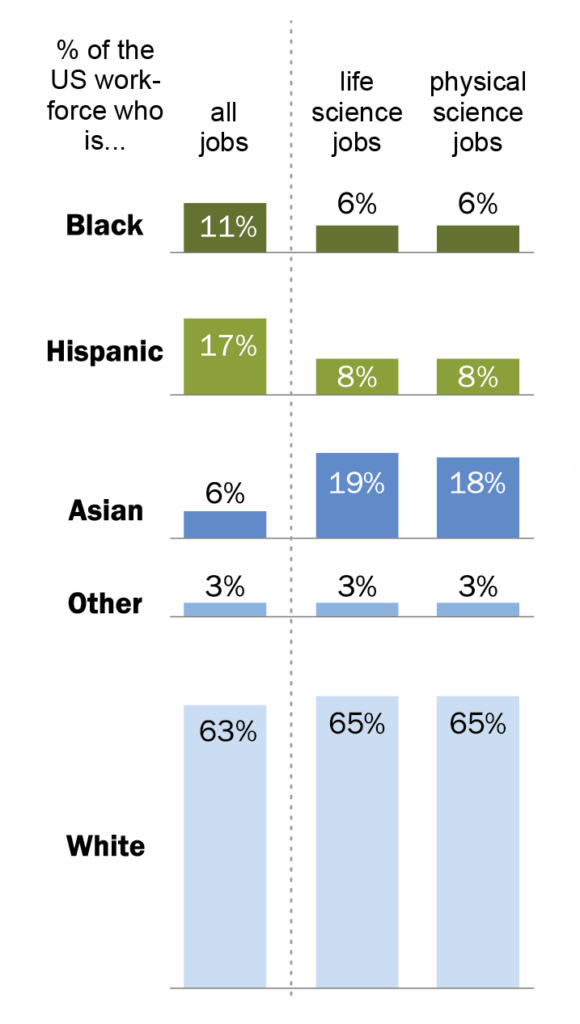

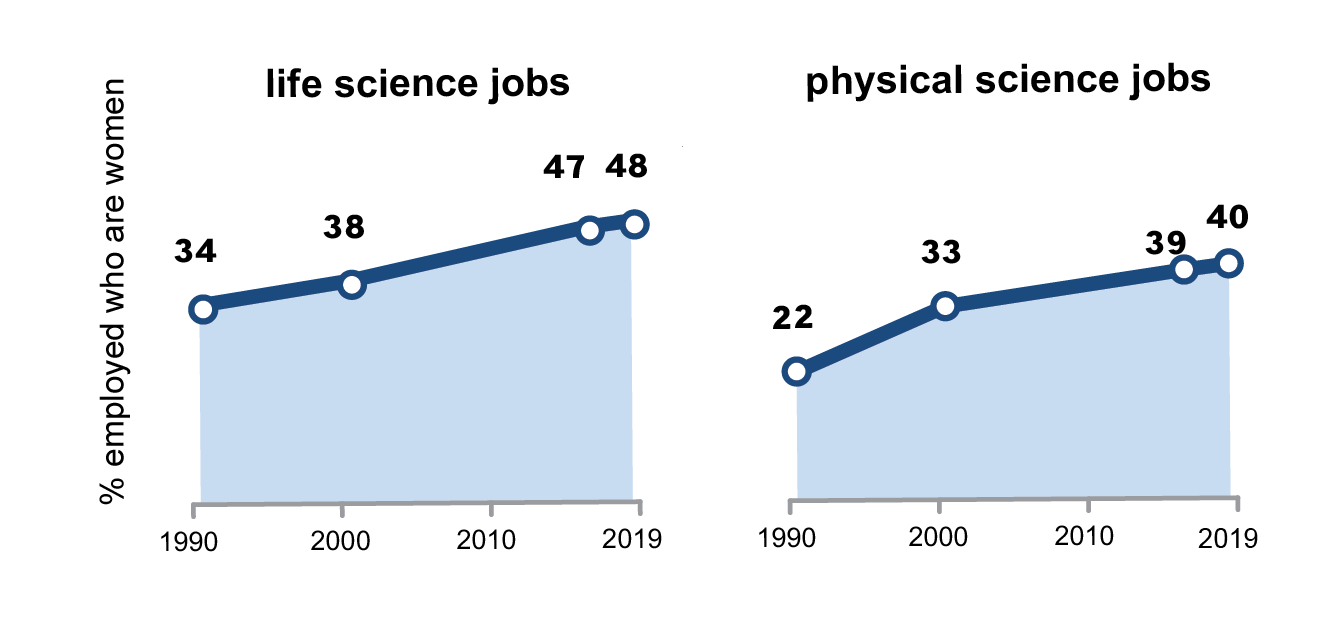

People from all over the world from all sorts of different cultures and backgrounds are a part of the scientific community, and science benefits from these different perspectives and contributions. At many points in history, Western science has been the exclusive domain of white men, but that is changing … slowly. For example, since people who identify as women represent about 50% of the U.S. population, they should make up 50% of scientists, too; over the past 30 years, women have come to hold a larger share of jobs in the life and physical sciences in the U.S. – though not half yet. And while Hispanic and Black people make up a significant percentage of the life and physical science workforce in the U.S. today, they still face barriers that lead to underrepresentation and are paid less than white and Asian workers.1 Many people are working on a variety of fronts to expand access and stamp out exclusion, but there is a long way still to go.2

Take a sidetrip

You can learn more about some of the barriers that people of color, women, and others face within science here.

Of course, “diversity” includes much more than just racial and gender identity – and the scientific enterprise benefits from participants with different cultures, religions, ages, sexual orientations, gender identities, disabilities, incarceration histories, classes, and so much more. Here are just a few of the ways that science benefits from diverse participants:

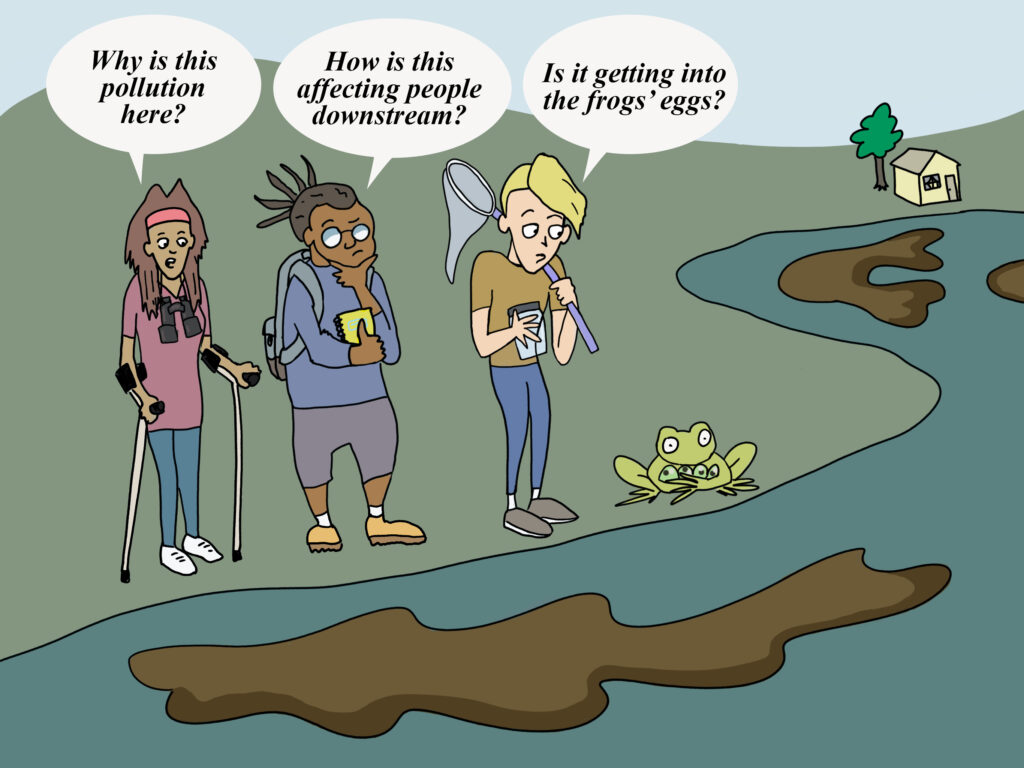

Diverse scientists ask diverse questions

While science can investigate any part of the natural world, progress is only made on those questions that scientists think to ask. Our backgrounds and identities shape the questions we ask about the world. For example, Black scientists are more likely to study health disparities than are white scientists, and female scientists are more likely to study pregnancy and education than are male scientists.3 If we want science to address the whole natural world and problems that affect all sorts of people, then we need all sorts of people to be able to participate in science.

Diversity facilitates specialization

Scientists have different strengths and different interests. People from different backgrounds may approach the same question in different ways. So, the biologist with a penchant for math, the biologist with an interest in human behavior, and the biologist who can’t get enough of microscopes and lab work can all focus on their strengths. While each might choose to tackle the same topic (say, human cognition), they will do so from different angles, contributing to a more complete understanding of the topic.

Diversity invigorates problem solving

Science benefits greatly from a community that approaches problems in a variety of creative ways. A diverse community is better able to generate new research methods, explanations, and ideas, which can help science over challenging hurdles and shed new light on problems. For example, scientists who study how science works (yes, that’s a thing!) have found that scholars from historically excluded backgrounds (e.g., African-American PhD students) produce more innovative research than their counterparts from overrepresented backgrounds.4 Similarly, because of their identities and backgrounds, Indigenous scientists often see ecological challenges in different terms than scientists from dominant backgrounds; in particular, they may be more likely to take a holistic approach, integrating many subdisciplines of biology and recognizing the interconnected nature of an environmental problem.5 Indigenous scientists also have access to valuable traditional knowledge built from generations of experience with and connections to a particular place, such as recognizing differences in subspecies that non-indigenous scientists might not.6 Diverse perspectives simply lead to richer and more exciting scientific discoveries.

NEURODIVERSE IDEAS

Scientist Temple Grandin studies animal behavior. She is well known for investigating how animals raised as livestock react to their surroundings and for developing ways to make our treatment of livestock more humane. Grandin is autistic and has explained in interviews and talks how this has deeply shaped her science. For example, she describes her own thinking as based in pictures, not words, and credits that aspect of her autism with helping her relate to livestock animals and focus on their visual perception.7 This was an important part of her early research, which showed how small visual elements in a slaughterhouse, like shadows, can cause stress for livestock. Grandin’s autism led to research and compassionate innovations in the livestock industry that might not have come about otherwise.

Diversity balances biases

Science benefits from practitioners with diverse beliefs, backgrounds, and values to balance out the biases that would occur if science were practiced by a narrow subset of humanity. As an example, consider the ongoing scientific investigation of climate change. With such a hot-button issue, personal beliefs about the environment, the economy, business, and politics could unwittingly bias one’s search for or assessment of the evidence. But science relies on a diverse community, whose personal views run the gamut: liberal to conservative, tree-hugging to business-friendly, and all sorts of combinations thereof. Scientists strive to be impartial and objective in their assessments of scientific issues, but when personal biases sneak in (and they are bound to – scientists are, after all, human!), a diverse scientific community can help keep them in check.

We should do all we can to support more different sorts of people becoming scientists, not only because everyone deserves to be able to pursue their curiosity and experience the joy of science, but also because we all stand to benefit from science informed and pushed forward by diverse perspectives. If scientists were all the same, scientific controversy might be rare, but we would learn less about a much smaller portion of the natural world. Science depends on diversity – and yet, science has been, and very often still is, exclusionary. Many people are beginning to recognize this and are taking steps on a variety of fronts to make science more inclusive – from training to hiring, from workplace culture to funding systems. There is a long road to travel before science will reflect the diverse societies in which it is embedded and serve the whole spectrum of the world’s inhabitants.

For an example of how diverse participants can help advance scientific knowledge, check out the story of Lynn Margulis, Cells within cells: An extraordinary claim with extraordinary evidence.

1Pew Research Center, April, 2021, “STEM Jobs See Uneven Progress in Increasing Gender, Racial and Ethnic Diversity.”

2 Tilghman, S., Alberts, B., Colón-Ramos, D., Dzirasa, K., Kimble, J., and Varmus, H. (2021). Concrete steps to diversity the scientific workforce. Science. 372: 133-135.

3 Hoppe, T. A., Litovitz, A., Willis, K. A., Meseroll, R. A., Perkins, M. J., Hutchings, B. I.,… and Santangelo, G. M. (2019). Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Science Advances. DOI 10.2226/sciadv.aaw7238

Kozlowski, D., Larivière, V., Sugimoto, C. R., and Monroe-White, T. (2022). Intersectional inequalities in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 119: e2113067119.

4 Hofstra, B., Kulkarni, V. V., Munoz-Najar Galvez, S., and McFarland, D. A. The diversity-innovation paradox in Science. (2020). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 117: 9284-9291.

5 Hernandez, J. (2022). Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes Through Indigenous Science. North Atlantic Books.

6 For example, see Stronen, A. V., Navid, E. L., Quinn, M. S., Paquet, P. C., Bryan, H. M., and Darimont, C. T. (2014). Population genetic structure of gray wolves (Canis lupus) in a marine archipelago suggests island-mainland differentiation consistent with dietary niche. BMC Ecology. 14: 1-9. For more on the potential future relationship between traditional and western scientific knowledge, see Reid, A. J., Eckert, L. E., Lane, J., Young, N., Hinch, S. G., Darimont, S. J. C., … and Marshall, A. (2020). “Two-eyed seeing”: an indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management. Fish and Fisheries. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12516

7 Richter, R. (2014). 5 Question: Temple Grandin discusses autism, animal communication. Stanford Medicine News Center. https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2014/11/5-questions--temple-grandin-discusses-autism--animal-communicati.html