Because science is a human endeavor, it benefits from our best traits – our curiosity, creativity, and perseverance. Unfortunately, it can also be affected by some of our worst motivations and beliefs – like racism, sexism, ageism, ableism, homophobia, and other forms of prejudice. These prejudices have shaped and continue to shape the course of science in many ways.

Scientists and scientific institutions have:

Built or used scientific “knowledge” to falsely justify prejudice and prejudiced actions

Scientists with racist, sexist, and otherwise biased agendas have pursued research in support of their ideas and actions, which include colonization, slavery, and genocide. For example, in the early 1950s, scientists that were part of the eugenics movement conducted what were often poorly conceived and biased studies, marshaling “evidence” aimed at ridding society of characteristics that they deemed undesirable. The traits targeted by the movement were based on wide-ranging prejudices, prominently towards those with physical and mental disabilities. Roughly 60,000 Americans were forcibly sterilized as a result of policies that grew out of eugenics research.1 Because science involves testing and retesting ideas in many ways, false ideas (e.g., that so-called “feeblemindedness” is a discrete and neatly heritable trait, that one race is more intelligent than another, that men have more logical minds than women do, or that being raised by a same-sex couple harms children) are ultimately shown to be just that – false. But when societal prejudices align with these false ideas, they can take longer to overcome and do more damage as they are used to justify cruel and unethical practices. Sadly, we still see these refuted ideas used to support racist and biased policies today – for example, when the NFL made it easier for white players to claim compensation for brain trauma than Black players, arguing that the two races should be judged on separate scales of brain function.2

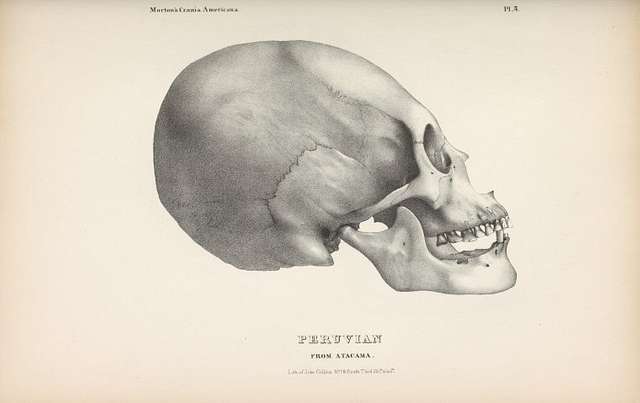

SAMUEL MORTON'S SKULL STUDIES

In the 1800s, researchers like American doctor Samuel Morton3 studied the skulls of people of different perceived races. He and many others wanted to make the case that white people had the largest brains and highest intelligence, and so were fundamentally better than people with other skin colors. Racist ideas like this had been around for a long time, but Morton and others tried to use science to prop them up. Morton’s investigations were based on the faulty assumption that brain size is an indication of brainpower and used techniques that scientists have since argued were biased.4 Morton’s personal racism shaped the questions he asked, his assumptions, his choice of research methods, and his interpretation of his results in ways that allowed him to justify his own (and his society’s) racist beliefs. And ultimately, it seems to have been effective. Morton’s work was championed by Southerners who claimed it justified enslavement of Black people.

Used prejudiced research and data collection methods

Scientific research has been conducted in biased ways that value some groups above others. This includes well known (and horrific) examples, such as studies in gynecology that involved performing surgeries on enslaved Black women without anesthesia and a study of syphilis that withheld information and treatment from Black participants for decades.5 Cases like these have motivated scientific institutions to put in place rules that protect people who participate in studies and ensure that research methods are fair. These important changes help, but biased research is an ongoing problem that needs to be continually guarded against.

Used scientific knowledge in biased ways

Scientists and others have used scientific knowledge in ways that are oppressive and that have unfair outcomes for members of some groups – and science is still used in these ways. Whether the unfair outcomes are intended or not, they are caused by the assumption that some groups are less worthy of care than others. Science, technology, and engineering are full of such examples – including the development of medical equipment that gives accurate readings for people with white skin but not for people with dark skin6 and facial recognition algorithms that consistently perform worse on young, Black women than on people from other groups.7 Scientists can do much more to ensure that the innovations that come from scientific knowledge are developed with all people in mind.

Not valued or credited scientific contributions fairly

In science, it is important to provide credit when building on the work of others. This helps scientists check the work, and importantly, it also affects who gets to do what research. Career advancement, award, and funding decisions are partly based on whose work receives credit from other scientists. Not giving proper credit could rob someone of a promotion or grant money to further their research.

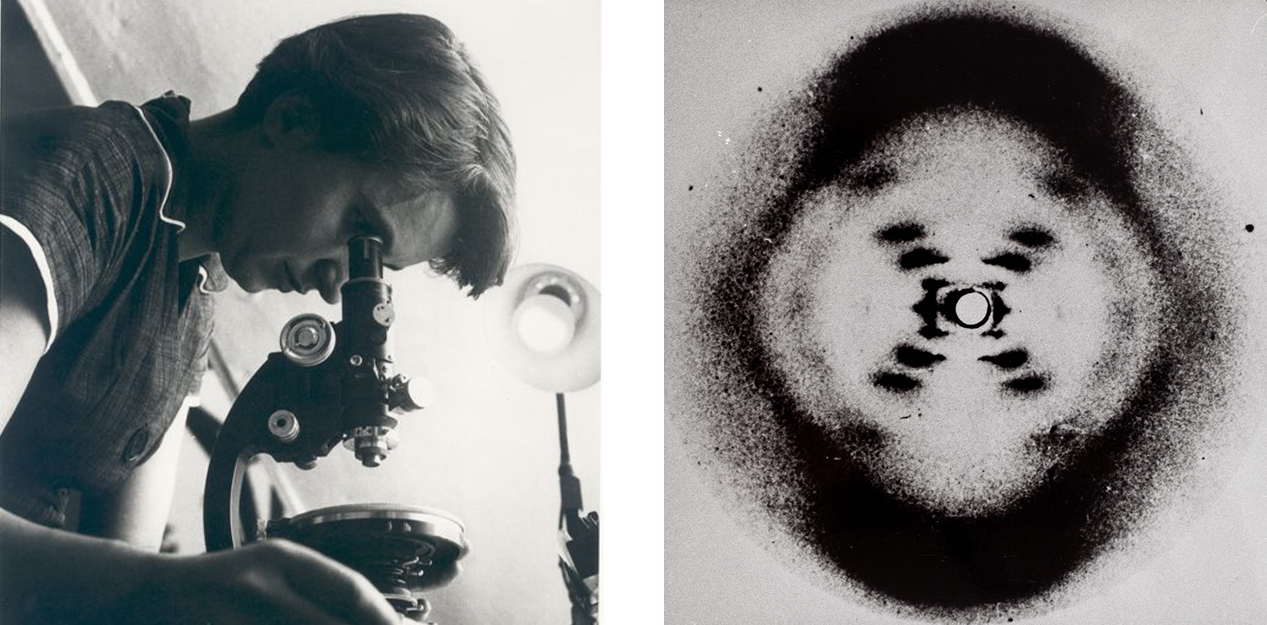

Unfortunately, because of individual and institutional biases, women, people from historically excluded groups, and others have not always received the credit they deserved in science. Infamously, James Watson and Francis Crick’s hypothesis about the structure of DNA was based on key evidence collected by Rosalind Franklin. Franklin was not given credit for that evidence when Watson and Crick published their hypothesis. This is now considered a serious violation of scientific ethics – but we only know about it because the discovery was such a pivotal one in the history of science.

In many cases, such biased oversights and exclusions go unnoticed by the broader scientific community. These unrecognized exclusions are particularly egregious with scientific knowledge originally generated by Indigenous people. For example, white scientists have routinely “discovered” species that were already well known to Indigenous people through direct experience and traditional knowledge. Western scientists have simply ignored and discounted the scientific knowledge already existing about these species in Indigenous communities.

WHAT IS COLONIALISM?

Colonialism is the theft of Indigenous lands and resources by settlers, which is accompanied by exploitation and genocide. Colonialism is a horrific and recurring theme in world history. It has also shaped and continues to shape the course of science. Scientists from Western countries have collected and continue to collect fossils, artifacts, plants, animals, and minerals from around the world and use them for their own studies, often without consulting or crediting, let alone investing in, including, or deferring to the local community. Western scientists have conducted medical research in developing countries and with Indigenous people, collecting genetic and other data from them, again extracting information – information that has generated large profits for pharmaceutical companies – without providing recompense to or sharing control with the source of that data, the local population. In the last few years, many scientists and others have taken a stand against colonial science. This means making a range of changes – from returning specimens and artifacts to their rightful caretakers to investing in the capacity of local people to shape, participate in, and lead research efforts in their own countries and communities.

Take a sidetrip

Take a side trip to explore articles about how natural history museums, which were often built through colonial science, can address this history and do better, and to learn about a new model for conducting research with Indigenous communities and knowledge.

Prevented or discouraged many groups of people from participating in or achieving at science

Science should be open and welcoming to everyone but is still very far from that ideal. A 2021 survey of working scientists around the world found that 27% experienced and 32% observed discrimination (including gender identity, age, racial, sexual orientation, disability, and religious discrimination).9 Because scientists are shaped by their societies and experiences, and because institutions perpetuate their own historical legacies, prejudice, discrimination, and exclusion can be embedded in scientific cultures.

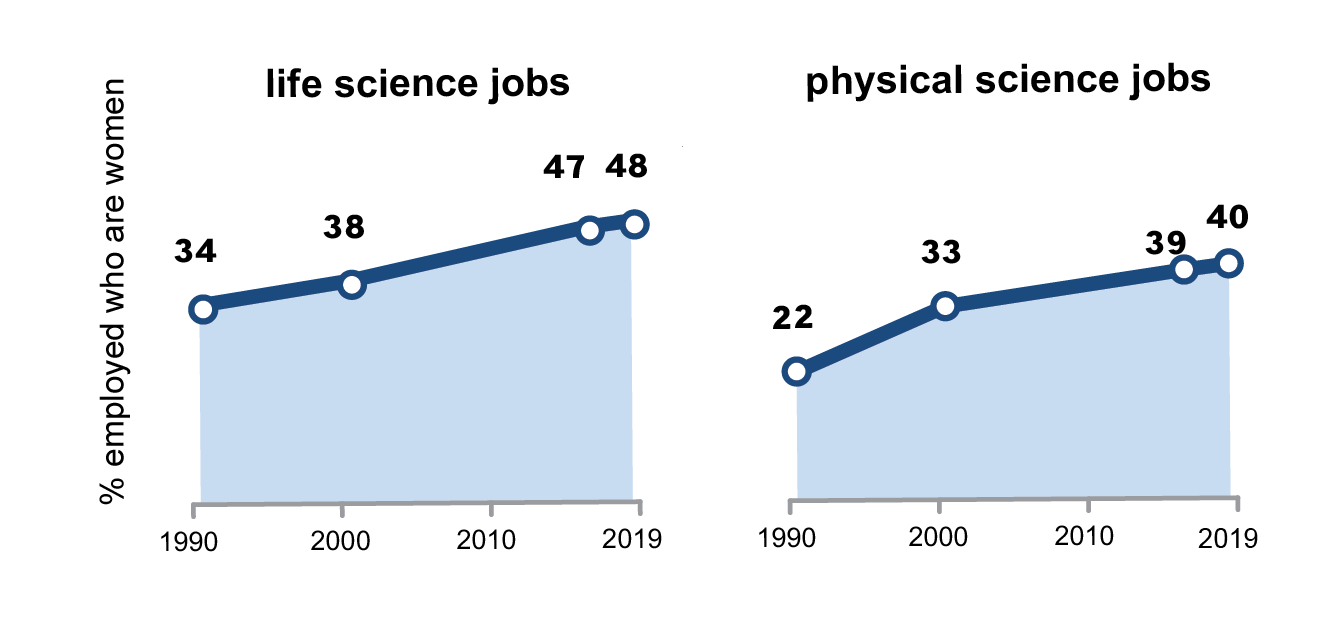

As a result of barriers like this, the people who do science for a living often don’t reflect the ethnic, racial, and gender makeup of the society around them. For example, in the U.S. in 2019, Hispanic people made up 17% of the workforce, but just 8% of life scientists. Similarly, women (almost half of the American workforce) held only 16% of jobs as astronomers and physicists.10

Similarly, on a global scale, many barriers exist to full participation and achievement. For example, 98% of scientific publications today are English-language, and many scientific conferences require presentations to be made in English.11 Yet, less than 8% of the world’s population speaks English as a first language.12 This makes it harder and costlier for most of the world to make scientific contributions and have those recognized. Another way that scientists create uneven barriers to achievement in science at a global level is through “parachute science” – when scientists from a higher income country “parachute into” a lower income country to do fieldwork, and then leave without communicating with or engaging local people.13 This practice disconnects local people from scientific data they could use to answer research questions important to them and creates reliance on external experts, all of which discourages local research efforts and makes it harder for people from lower income nations to achieve in science.

The ultimate causes of such discrepancies in participation and achievement are individual, institutional, and societal biases and their ongoing legacies, including colonialism. For most of its history, people of color, women, and other groups had to fight to participate in science, overcoming barriers that others (mainly white men) did not – and that’s still the case. Many scientists and non-scientists alike now recognize the lack of diversity in science as a problem and are working to change things. While more people from different backgrounds now participate in science than ever before, there is still a long way to go before science is truly inclusive.

SAME QUALIFICATIONS, DIFFERENT OUTCOMES

In a recent experiment, researchers sent out identical fake resumes to apply for research jobs in biology and physics. The only differences among the resumes were the names, which suggested that the applicant was female, male, Black, White, Asian, and/or Latinx (the categorizations used by the researchers in this investigation). This study uncovered many clear biases. For example, physicists evaluating the applications rated males, Whites, and Asians as more competent and hirable than females, Blacks, and Latinx people – despite the fact that their credentials were identical!14

Towards an unprejudiced science

As described above, science has been (and continues to be) shaped by racism and other forms of prejudice. While abhorrent in its own right, this history has also had negative effects on science itself, curtailing the diversity of its workforce and leading to distrust of science among some communities at the receiving end of this prejudice. Acknowledging where science has not lived up to its ideal of being unbiased is the first step of many in removing racism, sexism, and other forms of bias from the scientific enterprise. It will take a sustained effort on the part of scientific institutions to regain the trust they have lost, attract and retain diverse participants, and fix biased research practices and workplace cultures. This work to eliminate prejudice is worthwhile, not only because it is the right thing to do, but because society stands to benefit. When scientists aren’t trying to prop up false beliefs, when scientific knowledge is built, applied, and credited in fair ways, and when the scientific community is representative of the diverse societies in which it is embedded, science can build better explanations for more parts of the natural world, benefitting more people and communities.

- For an example of how diverse participants can help advance scientific knowledge, check out the story of Lynn Margulis,

- To learn more about how credit was (and was not) given in the discovery of the structure of DNA, check out The structure of DNA: Cooperation and competition.

- Take a side trip to review how science benefits from diverse participants.

- Explore this reading list to see what scientists are saying to each other about prejudice and exclusion in science.

1Norrgard, K. (2008) Human testing, the eugenics movement, and IRBs. Nature Education 1: 170.

2Leigh, S. (2020). ‘Race norming’ blamed for denying payouts to ex-NFL players with dementia. UCSF. Accessed July 31, 2022 at https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2020/12/419426/race-norming-blamed-denying-payouts-ex-nfl-players-dementia

3Morton, S. G. (1839). Crania Americana. Philadelphia: J. Dobson.

4Gould, S.J. (1981). The Mismeasure of Man. 1st ed. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Lewis, J.E., DeGusta, D., Meyer, M.R., Monge, J.M., Mann, A.E., and Holloway, R.L. (2011). The mismeasure of science: Stephen Jay Gould versus Samuel George Morton on skulls and bias. PLoS Biology. 9: e1001071.

Weisberg, M., and Paul, D. B. (2016). Morton, Gould, and bias: “a comment on the Mismeasure of Science.” PLoS Biology. 14: e1002444.

5J. Marion Sims performed these gynecological experiments in the 1800s. The Tuskegee syphilis study was conducted between 1932 and 1972.

6Moran-Thomas, A. (2020). How a popular medical device encodes racial bias. Boston Review. Accessed July 31, 2022 at https://bostonreview.net/articles/amy-moran-thomas-pulse-oximeter/

7Klare, B. F., Burge, M. J., Klontz, J. C, Vorder Bruegge, R. W., and Jain, A. K. (2012). Face recognition performance: role of demographic information. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security. 7: 1789-1801.

8Fawzy, A., Wu, T. D., Wang, K., Robinson, M. L., Farha, J., Bradke, A., … and Garibaldi, B. T. (2022). Racial and ethnic discrepancy in pulse oximetry and delayed identification of treatment eligibility among patients with COVID-19. JAMA Internal Medicine. 182: 730-738.

9Woolston, C. (2021). Discrimination still plagues science. Nature. Accessed August 1, 20222 at https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03043-y

10Pew Research Center, April, 2021, “STEM Jobs See Uneven Progress in Increasing Gender, Racial and Ethnic Diversity.”

11Gordin, M.D. (2015). Scientific Babel. University of Chicago Press.

12Noack, R., and Gamio, L. (2015). The world’s languages, in 7 maps and charts. The Washington Post. Accessed August 1, 2022 at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/04/23/the-worlds-languages-in-7-maps-and-charts/

13Stefanoudis, P. V., Licuanan, W. Y., Morrison, T. H., Talma, S., Veitayaki, J., and Wodall, L. C. (2021). Turning the tide of parachute science. Current Biology. 31: PR184-r185.

14Eaton, A. A., Saunders, J. F., Jacobson, R. K., and West, K. (2020). Advancement of scholars in STEM: professors’ biased evaluations of physics and biology post-doctoral candidates. Sex Roles. 82: 127-141.