Concept

Scientific knowledge is open to question and revision as new ideas surface and new evidence is discovered.

By Taormina Lepore

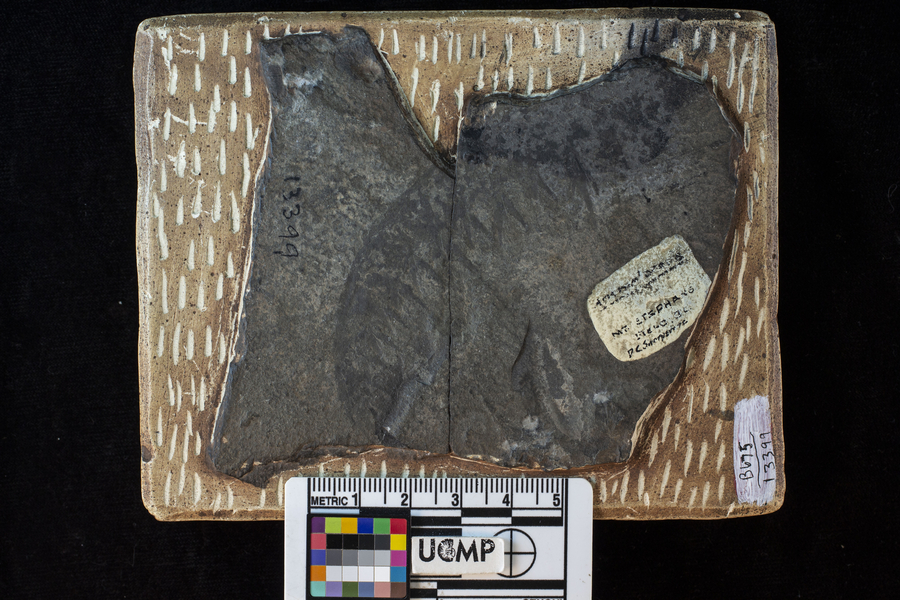

When you look at this fossil specimen from Earth’s ancient oceans, what do you see? Maybe the first thing you notice is the shape, with sharp points jutting out from a curved and mysterious form. If you could touch it, you might feel the smoothness of the black rock and the outline of tiny, spindly “legs” coming off of an armored and segmented body.

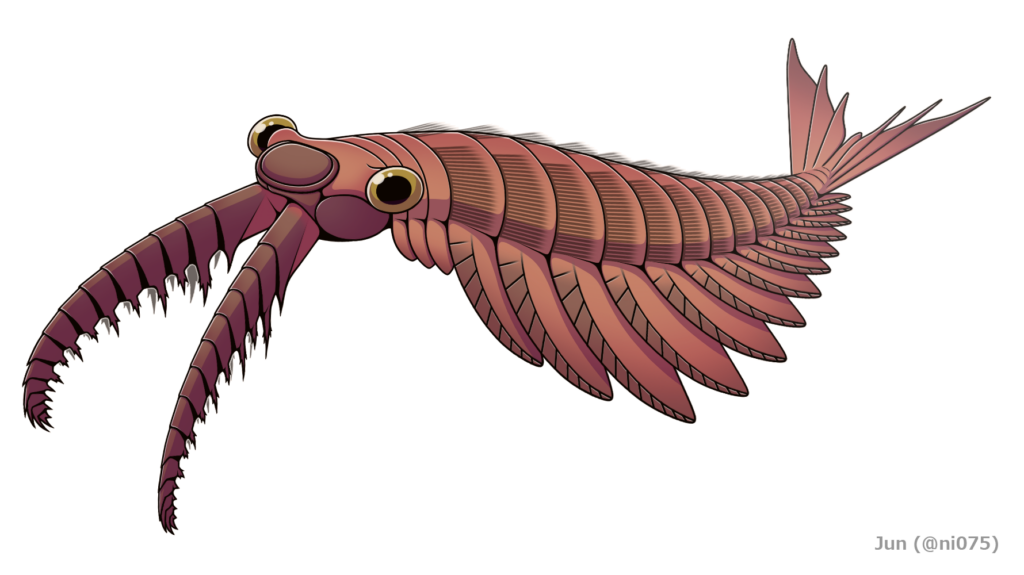

It looks a little bit like a shrimp, with sharp pointed legs. At least, that’s what researcher JF Whiteaves thought. He first described this creature in the 1890s, and named it Anomalocaris – anomalo meaning ‘strange or irregular’ and caris meaning ‘shrimp’. But further study would reveal it to be far more than a shrimp-like scavenger on the seafloor.

We now know that those sharp “legs” aren’t legs at all. They are part of the hook-like prey-capturing devices of a top predator that lived 520 million years ago during the Cambrian Period, when our planet was teeming with marine life.

For almost 100 years, researchers had found the fossilized appendages and other shelly parts of Anomalocaris, which often separated from the animal after death and are common in the fossil record. These detached body parts were often confusing. One isolated piece of Anomalocaris was even misidentified as a fossil jellyfish! These distinct fossil parts were all connected in the mid-1980s when researchers Derek Briggs and Harry Whittington described the whole body fossil of Anomalocaris, including its hook-like appendages. Reinterpreting all these different fossils as parts of the same animal revealed that Anomalocaris is a distant cousin of modern shrimp and other crustaceans, and belongs to a group known as radiodonts.

The specimen pictured above is in the collections of the University of California Museum of Paleontology and is from the famous Burgess Shale locality in British Columbia, Canada. The Burgess Shale records a time when animal life was expanding and evolving into a dizzying variety of shapes and sizes. Paleobiologists call this period of time the Cambrian Explosion, because of how much diversity appears in the fossil record. Although this species was only about 2 feet (60 centimeters) long, it was, relatively speaking, a huge predator for its time, feeding on smaller marine animals. Anomalocaris was an early evolutionary experiment in meat-eating — like the tiny Tyrannosaurus rex of its day.

Scientists make observations and draw conclusions based on the evidence available. But as we have seen with Anomalocaris, sometimes new observations and further evidence, like collecting more fossils or reexamining fossils already in museum collections, can shift our interpretations and change our conclusions. This is a normal part of the process of science. Anomalocaris was not the strange shrimp we thought it was, but the truth turned out to be even stranger!

Citation

Whittington, Harry B. and Briggs, Derek E.G. (1985). The largest Cambrian animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British-Columbia. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B309569–609. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1985.0096

De Vivo, G., Lautenschlager, S., & Vinther, J. (2021). Three-dimensional modelling, disparity and ecology of the first Cambrian apex predators. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 288(1955), 20211176. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspb.2021.1176?download=true

Whiteaves, J. F. (1892). Description of a new genus and species of phyllocarid crustacea from the Middle Cambrian of Mount Stephen, BC.

https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=gEcbAAAAYAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA206&ots=8n2OqpBsHb&sig=j4jhFGU0dO5AFTEGfdf0T0p8QuE