Concept

The scientific community is global and diverse.

Paleontologist Dr. Ashley Dineen studies marine invertebrate fossils and is the Senior Museum Scientist of Invertebrate Paleontology at the University of California Museum of Paleontology. She shares her story of how she became interested in science, and the various global communities she’s worked with along her journey.

I wasn’t a dinosaur-obsessed kid. I was really interested in nature and how the world worked. That included everything! Plants, animals, the weather. I grew up in Wisconsin and was obsessed with the tornadoes and thunderstorms that would pass through the region. When I started at my local community college, I knew that I wanted to study natural science. Because of my interest in the weather, I started off as an atmospheric science major, but the more I got involved in the field, the more it wasn’t quite what I expected.

When I was a sophomore, I took a geology course as one of my atmospheric science prerequisites. I ended up really liking it, and that professor encouraged me to really keep going with geology. So when I transferred to University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, my junior year, I stuck with geology! I was interested in sedimentology and hydrology, how sediments and water interact, which is a big topic for the Great Lakes region in the U.S. Then, I took a field paleontology class that went to the Bahamas, and we had to do a project while we were there. I compared the fossilized Bahamian coral reefs to the living coral reefs, and I kind of fell in love with all the shells and marine organisms! I found it so interesting that you could link the past with the present, and interpret how the environment had changed over time.

When I got back to eastern Wisconsin, far from the Caribbean, I started to think about how I could keep following my new passions. My plan was to get a job in geology consulting in hydrology, because that felt like the only job option for a geologist in the Great Lakes region. But one of my professors took me aside and said, hey, had I ever considered graduate school? I said no, I couldn’t afford something like that. The professor explained that my tuition could be paid for if I taught classes for the university where I studied. I had made it all the way through my undergraduate program without knowing this was possible!

A couple of other professors in my geology program contacted me, and said they’d like me to be involved in this particular project in Argentina, on sedimentology and paleontology. How could I say ‘no’? That ended up being my Master’s project, half in paleontology and half in stratigraphy and sedimentology, the study of how rocks form and how layers of rock can tell a story. We worked with an international team of scientists there, from the University of California Davis and the Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio in Argentina. I really appreciated how these professors contacted me with an opportunity, and to this day, I try to tell my undergraduate museum students about new opportunities in paleontology they could pursue.

During my Master’s, I realized I wanted to keep up with paleontology research. When I started thinking about a PhD, I knew I wanted to work in collections or in a museum, because that was one of my earliest exposures to science as a kid. I loved natural history museums. I knew I probably needed a PhD to be a museum curator, so I applied to various schools, but ended up staying in Milwaukee with my Master’s program advisors. I studied the Permo-Triassic mass extinction and collected specimens in the field from all over the world, including China, Italy, and the Western US, which ended up in museums. Now that I’m working here in the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP), I recognize there are so many fossil specimens that are sitting in collections here and all around the world. There’s so much left that needs to be looked at!

Working in museum collections can bring lots of interesting surprises with it as you uncover what’s in the collection drawers from years past.

This is one of my favorite parts of the job! Finding these hidden things in the collections. What I particularly like about UCMP’s invertebrate collection is that there’s such a rich collection spanning from the 1860s to today, which makes it historically important in a different aspect. Only a handful of people have managed the invertebrate collection as a curator over the years, since a lot of the early attention at the museum went to the vertebrate collections and the big dinosaurs and mammals. Lots of people around the world look to our collection for answers to scientific questions on invertebrate fossils. Now that we have paid staff and students who dig through these drawers a bit more, multiple new species could be discovered and described from the invertebrate collections.

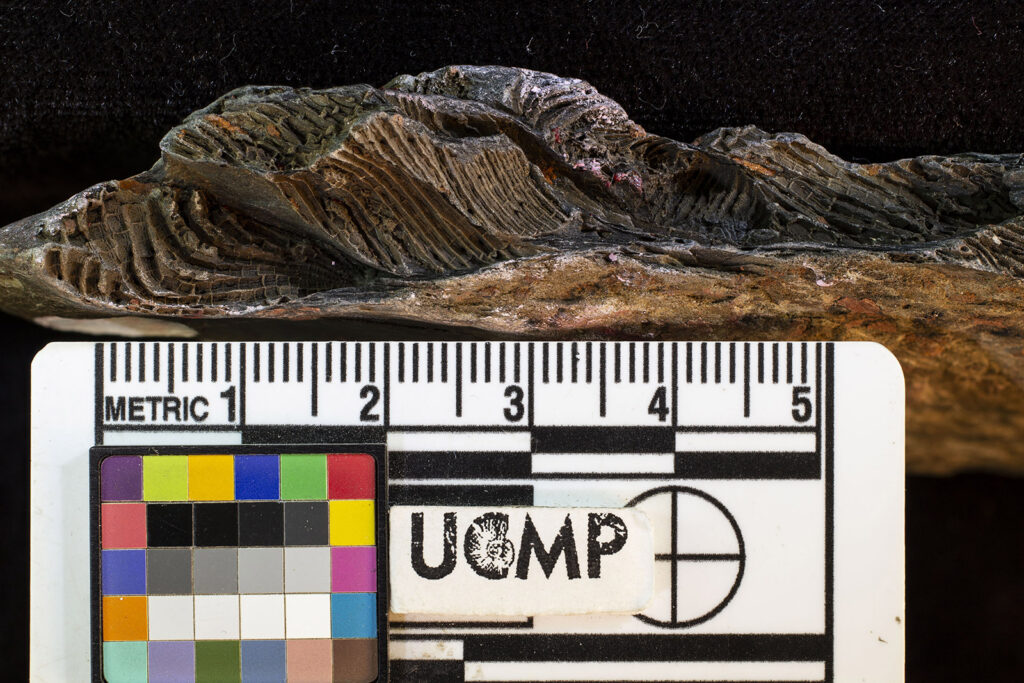

We also have some invertebrate fossils that no one else has. One example of this uniqueness is our collection of helicoplacoids – they’re super weird relatives of sea stars and sand dollars, and look a bit like a fingerprint. We have a big collection here from our former museum director, Dr. J. Wyatt Durham, who discovered them in the early 1960’s.

Thinking about how global museum communities can come together and solve problems, there is this case of a mysterious helicoplacoid specimen that went missing in our museum. A researcher had reported a helicoplacoid specimen from British Columbia, Canada – very far away from where they’re usually found in a small section near the border of Inyo County, California, and Nevada. But even though we had lots of notes about this supposed Canadian helicoplacoid, the fossil itself had been missing since 1983! No one could find it in our collections, no matter how hard we looked, and the original British Columbia site it came from was only accessible by helicopter. It felt like this fossil had gone missing for good.

I was reading through a paper on helicoplacoids from 2006, which had some information about the mystery fossil and its origins in Canada. It dawned on me – we have plenty of unidentified helicoplacoids in our collection. I had a hunch that this mystery fossil might be sitting somewhere in a tray of unusual helicoplacoid specimens that were in our lab, just waiting for further identification. And when I went back to search for it in that tray, there it was! I’m still experiencing the joy of that moment. A 40-year mystery solved. I wrote to the British Columbia museum that had originally sent us the specimen, and we were able to return it through our global community of fossil curators.

The British Columbia helicoplacoid might even be a new genus or species. It’s really cool. This specimen expanded the distribution of the helicoplacoids from one spot on the border of California and Nevada to the entire ancient west coast, all the way up to British Columbia.

Working together with scientists from other parts of the world with different backgrounds and identities makes science a better community – and, consequently, better able to build scientific knowledge about the whole natural world. Ashley’s journey in science is just one example of how scientists can help one another succeed and how the global community of scientists can collaborate to answer scientific questions.