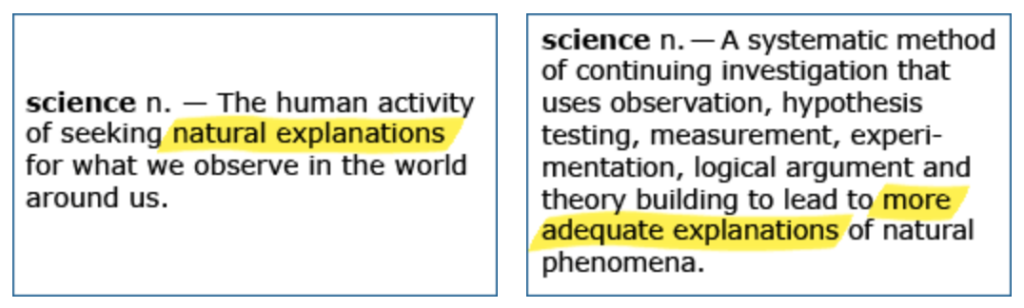

In 2005, the Kansas State Board of Education enacted a seemingly minor change in the state’s science teaching standards. Up to that time, science had been defined in a standard way as “the human activity of seeking natural explanations for what we observe in the world around us.” After the change, the definition for science became “a systematic method of continuing investigation that uses observation, hypothesis testing, measurement, experimentation, logical argument and theory building to lead to more adequate explanations of natural phenomena.” Scientists, science teachers, and many members of the general public objected to the change. As a result of their protests — and after the election of a new State Board of Education — in 2007, the definition was shifted back to the original. But what’s the big deal? After all, an activity about seeking natural explanations had become an activity about seeking more adequate explanations of natural phenomena — what’s the difference? A lot, it turns out.

The key issue here is that the prior definition restricted the types of causes that science can propose and investigate to natural ones, emphasizing that science cannot study supernatural explanations. To see why this is important, consider the fanciful idea that gravity is caused by undetectable, supernatural gnomes connecting everything in the universe together with invisible chewing gum. That might or might not be true, but under the standard definition, science can’t study that explanation since it is supernatural. The definition with the 2005 change, however, allows any kind of explanation, including the magical and supernatural, into the realm of science so long as it deals with natural phenomena. According to the changed definition, the gnome-based explanation for gravity could be included in science class! Though we’re obviously joking about the gnomes, the issue is a serious one. The shift in definition would have opened the doors of Kansas science classrooms to any group looking to deliver their views of supernatural causation to students in public schools and to pass those views off as legitimate science.

The key issue here is that the prior definition restricted the types of causes that science can propose and investigate to natural ones, emphasizing that science cannot study supernatural explanations. To see why this is important, consider the fanciful idea that gravity is caused by undetectable, supernatural gnomes connecting everything in the universe together with invisible chewing gum. That might or might not be true, but under the standard definition, science can’t study that explanation since it is supernatural. The definition with the 2005 change, however, allows any kind of explanation, including the magical and supernatural, into the realm of science so long as it deals with natural phenomena. According to the changed definition, the gnome-based explanation for gravity could be included in science class! Though we’re obviously joking about the gnomes, the issue is a serious one. The shift in definition would have opened the doors of Kansas science classrooms to any group looking to deliver their views of supernatural causation to students in public schools and to pass those views off as legitimate science.

Modern science does not deal with supernatural explanations because they are not scientifically testable — in other words, there’s no way to gather evidence that would help us determine whether or not the explanations are accurate. In contrast to supernatural explanations, natural explanations generate specific expectations that we can compare to evidence from the natural world in order to determine whether the explanation is likely to be accurate. For example, an object’s acceleration due to gravity increases as the mass of the object increases. That explanation for one aspect of gravitational attraction generates specific, testable expectations. If the idea were accurate, a baseball and a much heavier lead ball of the same size should fall at different rates, with the lead ball experiencing a larger acceleration. We can perform this test, and when we do, we will find that the expectation (falling at different rates) does not match our observations, providing evidence that the idea may be incorrect. Now, consider our far-fetched, supernatural explanation for gravity — gnomes with chewing gum. Would they attach the same strength of gum to a baseball and a lead ball? Would they attach extra strength gum to the lead ball, causing it to fall faster? Who knows what supernatural beings wielding magical chewing gum would choose to do? Regardless of what we observe when we drop the two balls, we can always imagine a way to chalk it up to the gnomes. Supernatural explanations, by their very character, cannot be tested with the methods of science. That doesn’t mean that they are wrong; they are simply outside the realm of what science can legitimately investigate. Any effort to redefine science to include supernatural explanations is working at cross purposes to science’s main goal: to build reliable knowledge about the natural world based on natural explanations.