Medicine has benefited from scientific study for many years. We only have to look into the recent past to see how important medical studies are in our daily lives: antibiotics, vaccines, and vitamins mean we don’t have to live with gangrene, polio, scurvy, and other diseases that crippled our ancestors. In Europe and the US, medicine developed alongside science, so it isn’t surprising that the two disciplines influenced one another. Not all medical traditions, however, have had such a close relationship with science. Herbalism, homeopathy, and traditional Chinese medicine, among others, are rooted in traditional cultures and spirituality. Acupuncture is a technique of traditional Chinese medicine that has been used for more than 2000 years. Some claim that acupuncture has been “proven” to work, and others write it off as quackery. Can science help us figure out whether acupuncture works, and if so, how?

Acupuncture is purported to have outcomes well within the realm of the natural world, and since science deals with natural phenomena, it can study these effects. Over 4,000 scientific studies have been published on the efficacy of acupuncture for disorders ranging from tennis elbow1 to post-traumatic stress disorder.2 Evidence suggests that acupuncture can effectively treat some symptoms like nausea and pain3 — though not generally the underlying causes of these symptoms. For example, it can help with the pain caused by tennis elbow, but is not thought to help treat the inflammation and tendon tears that are the root cause of this injury. Nevertheless, relief from symptoms like pain and nausea are valuable medical outcomes in their own right.

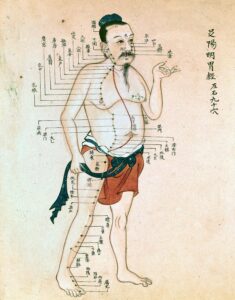

So scientific investigations can tell us when acupuncture works, but can they tell us how it works? The answer depends on what sort of explanations we are interested in investigating. According to traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture is based on the idea of Qi (pronounced and often spelled Chi), which is envisioned as a type of life-giving energy that circulates through the body in special channels. Acupuncture is thought to release blockages in these undetectable channels, restoring the flow of Qi through the body. According to this view, Qi is a mystical force that cannot be sensed or observed — and because science focuses on testing ideas about the natural world with evidence obtained through observation, these aspects of acupuncture can’t be studied by science.

Of course, when acupuncture was first developed more than 2000 years ago, we understood much less about our bodies and had fewer tools of science at our disposal. Modern scientists studying how acupuncture works do not approach it as a mystical process. Instead, they make careful observations to learn more about acupuncture’s natural, physiological basis. This research is ongoing, but results so far suggest that endorphins — proteins naturally produced by the body — play some role in the process. Endorphins have a chemical structure similar to that of morphine or opium and, like those drugs, are known to block pain. Acupuncture may stimulate the production of these and other compounds that affect how the brain perceives pain.

Although some aspects of acupuncture therapy (its efficacy and physiological mechanism) can be studied by science, this doesn’t mean that scientific research supports or rejects the use of acupuncture as a medical treatment across the board. On the contrary, it means that science can tell us if, when, and how acupuncture works. So far, evidence supports its efficacy for some medical problems — especially certain kinds of pain. Research into how acupuncture relieves pain is still in its early stages and has not yet definitely answered the question. The study of pain is complex, in part, because it must rely on people’s reports of their subjective experience. Studies of acupuncture are further complicated by the difficulty of finding an appropriate placebo. Despite these challenges, ongoing scientific research is likely to shed further light on acupuncture therapy.

Learn more about what topics science can study in our section on what science is.

1Tsui, P., and M.C.P. Leung. 2002. Comparison of the effectiveness between manual acupuncture and electro-acupuncture on patients with tennis elbow. Acupuncture and Electro-Therapeutics Research 27(2):107-117.

2Hollifield, M., N. Sinclair-Lian, T.D. Warner, et al. 2007. Acupuncture for posttraumatic stress disorder — A randomized controlled pilot trial. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 195(6):504-513.

3Acupuncture. NIH Consensus Statement Online, 1997 Nov 3-5, 15(5):1-34.